Corresponding Author: Christopher Beeson

Email: Christopher.Beeson@ucdenver.edu

Institutional/Organizational Affiliation: University of Colorado Denver College of Arts & Media, Film & Television Department Program Manager / Lecturer

Abstract

Assuming no prior disposition toward the word ‘adjunctification’ in use or meaning, this essay explores the origins and deployment of adjunctification as a term, its use as a signifier, and as a contextual lens that defines an inflection point in the identity and function of The University. Adjunctification is a term describing a quantitative change in the balance of instructors in any given university who are on tenure track versus those who are not. Adjunctification is also a signifier which by its intentionally negative definition characterizes this situational change in balance as both quantitative and qualitative. Being commonly accepted as representing these functions and meanings, adjunctification may then also be used as a lens through which current issues within academia are interpreted: groups of individuals are sometimes characterized as opposing ‘factions’ in the context of adjunctification, but this is merely a symptom of policies that have fractured the identity and purpose of The University. Given that adjunctification transcends individual concerns and is a primary driver of critical systemic issues at the institutional level, we then explore its meaning in the context of institutional identity: when The University is viewed as a cultural hegemony (through the lens of historical materialism), adjunctification is the crisis which has fundamentally disrupted its foundational intent and structure. Moving forward from this conclusion, we introduce and explore the integral role of ethics in restructuring The University.

Key Words: adjunctification, institutional identity, cultural hegemony, tenure, adjunct, historical materialism

Preface

This is an essay of inquiry, not a formal research paper. It was a project undertaken to understand what it means when we employ the term ‘adjunctification,’ its sometimes-confusing uses, how it shapes and defines socio-political and economic dynamics, and how it functions in the framework of four-year institutions of higher education. I am a product of these institutions and have worked in them full time for ten years as an administrator and an instructor. I have experienced adjunctification in practice, have seen valued colleagues suffer from its policies, and have participated in meetings where those ‘personnel’ decisions are made. As someone who cares deeply about the fundamental noble mission of higher education and those who support it – to serve society with equity in pursuit of knowledge, truth, and beauty – I often find it difficult to square that with policies that can seem restrictive and demeaning toward the adjuncts meant to embody that mission on behalf of their institutions. In trying to understand adjunctification from a position of neutral interest I see what adjunctification was meant to do (temporarily bridge rapidly expanding gaps in teaching staff) but I also see the damage it has caused as a stop-gap policy that has become commonplace and increasingly dominant. It is difficult not to feel like there is some sinister institutional force at work. But there isn’t. Adjunctification is an imperfect temporary solution that has become a practical and existential problem for The University (any four-year institution of Academe) to reckon with. Addressing the various issues with adjunctification requires us to examine the purpose and function of The University. In this essay I characterize The University as a cultural hegemony (a set of ideologies that maintain a capitalist state), using the mechanisms of historical materialism to illustrate the following point: when the economic base of a social institution shifts, so do its culture and politics. Adjunctification fractures The University on economic and cultural levels equally, and it is the primary inflection point in our current complex institutional crisis.

The exclusionary system of tenure is at odds with the transient positioning of adjuncts because adjuncts are often not provided the same rights and privileges as tenured faculty. This creates a (perceived) class-society conflict. As the number of adjunct / contingent instructors grows and tenured faculty numbers decline, institutions of higher education become further conflicted between the economic demands of providing ‘education for all’ (by employing less expensive adjunct instructors) and preserving the system of checks and balances between tenured faculty and upper administration. These dynamics place academic integrity at risk and threaten the cultural fabric of The University. Adjunctification has resulted in a fundamental change in the ‘mode of production’ in higher education (its economic foundation), which has flipped the dominant organizational premise of The University’s superstructure into one based on economics rather than on the pursuit of truth, beauty, and knowledge. This unsustainable position, a fracture in identity and purpose, must somehow be resolved. The University cannot continue with ‘education for all’ as its foundational ethic and unchecked growth as its model because the money simply isn’t there to support it. Adjunctification is not the solution to this. But it is the touchpoint from which solutions must proceed.

As someone with a long career in higher education, I understand this thesis may feel naive or overstated. However, I believe it accurately describes the existential crisis adjunctification has created within four-year institutions. Fundamental ideals of Academe still drive individuals to pursue advanced degrees even though the market for advanced degrees within higher education’s ranks is over-saturated. Adjuncts are a low-cost solution to address the rising economic costs of sustaining the infrastructures of higher education. But this solution reduces the value of the ‘products’ of higher education – those with advanced degrees who wish to teach and perform research. The ideals that formed the superstructure of The University have been subsumed by the economics of sustaining their pursuit. This is not a research paper designed to contribute data sets or land citations. It is instead an earnest attempt to start from zero on this topic from my position inside the system. I believe there are ways to disrupt this erosion and transform The University into a new, sustainable version of itself that does not need to make these compromises. Ethics must be integral to this process, or the foundational mission of higher education will remain in jeopardy. We must consider radical solutions.

Adjunctification: Definitions

‘Adjunctification’ is a complicated concept for which the intended nuance is often dependent on user and context. Therefore, it is important to make these meanings clear before exploring the topic itself.

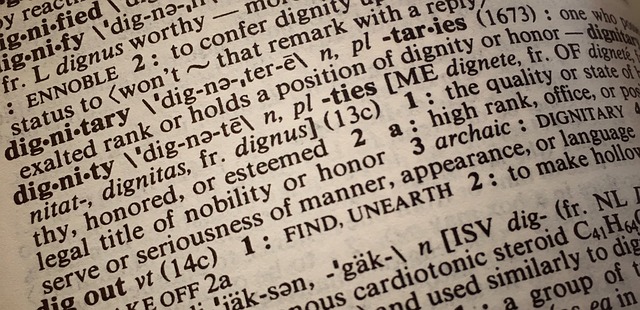

When parsed directly, ‘adjunctification’ (not yet listed officially in Merriam-Webster) literally means ‘the process of becoming adjunct.’ In that definition, what is meant by ‘becoming adjunct’? The word ‘adjunct’ in this context means “…attached in a subordinate or temporary capacity to a staff: an adjunct professor” (Merriam-Webster, 2022.). This definition contains the important connotation that adjunct faculty are ‘subordinate,’ making tenured faculty ‘dominant.’ Following this logic, ‘the process of becoming adjunct’ describes when the majority of faculty within an institution are changing from ‘dominant’ to ‘subordinate.’ These class and stature distinctions are an important part of how adjunct faculty perceive their positions and how they are often perceived by the institution. It’s important to keep in mind that ‘adjunct’ often describes only part-time employment status. However, in the context of higher ed, ‘adjunct’ also describes a range of ‘contingent’ faculty who are full-time, though often under term-limited contracts that are renewable. These faculty include instructors, lecturers, clinical / research track, visiting professors and graduate assistantships, all of which are non-tenure track positions. (In the context of most discussions about adjunctification and for purposes of this essay, I believe this is a sufficiently defined, if somewhat broad, subset).

The only etymology I could locate is with the compound term first appearing in a 1999 research paper by Arthur Sowers, Ph.D. (biology), titled PhD Revolutionary and Other Cop-outs, “re: …the adjunctification of the profesoriate (sic).” Subsequent etymology shows the term being employed in various contexts: “the problem of adjunctification,” “the classic victim of adjunctification,” “adjunctification …raises some concerns” (Wordsense, 2023.). What and who then are these ‘problems, victims, and concerns’ of adjunctification? In each of these contexts the term is employed to describe a process wherein the number of ‘subordinate’ faculty (adjuncts) is increasing while ‘dominant’ faculty (tenured) is decreasing. The process of adjunctification is one that causes personal, professional, and institutional issues.

So: ‘adjunctification’ is a term that describes (1) a quantitative ‘human resources’ process, and (2) is also qualitatively used to indicate a general situation of concern. Also consider this definition: [adjunctification is] “The tendency of universities to have as many faculty members as possible be adjuncts (who receive lower pay, benefits, lack tenure, etc.)” (Wiktionary, 2022.). This ‘tendency’ indicates a disposition of action, assigns it specifically to universities, and defines who is negatively affected by it. Adjunctification is therefore primarily used in a pejorative context connoting a system, process or tendency that produces negative effects. It is quantitative, qualitative, and can be used to characterize an active disposition of four-year institutions of higher education.

Factions and Dispositions of Adjunctification

When institutions of higher education begin to replace tenured positions with non-tenured adjunct positions, it’s fiscally positive for the institution in terms of fewer long-term commitments such as salary, benefits, retirement, physical offices, research funding, etc. Using adjuncts as a cost-effective means to scale growth was the original motivator:

The move toward hiring more part-time and non-tenure-track instructors began about 50 years ago. …in 1969, roughly 78 percent of faculty members at colleges and universities in the U.S. held tenure or tenure-track positions. Non-tenure track or adjunct roles accounted for about 22 percent. …College attendance grew sharply in the 1960’s and ’70’s due to federal financial aid programs and the GI Bill. …In academia, college tuition rates and fees rose faster than the inflation rate. Private loans began to replace federal grants as the primary source of financial aid for students from middle-class and lower-class backgrounds. As a result, colleges and universities started losing state funding. To cut costs, schools decided to swap out tenured and full-time teaching jobs for a cheaper option: adjunct and part-time professors. (Inside Scholar, n.d.)

Adjuncts (including part-time contingent faculty) don’t enjoy most or, on occasion,any of the benefits provided to tenured faculty. They generally have the same educational qualifications as tenured faculty, provide the same level of teaching, and are often asked to provide unpaid ‘invisible’ service (committees, student advising, special events and projects), sometimes to make up for the tenured faculty they replace. This group of academic professionals who make up an increasingly large percentage of the teaching community (44% of 1.5 million total faculty in 2020 (NCES, 2022)) are both fiscally and professionally marginalized: not only do they receive far less compensation and security, their status in the academic community is also perceived as ‘subordinate’ to tenured faculty. They are undervalued, unprotected, and often characterized as ‘invisible.’

Also consider the political status of adjuncts, part-time contingent faculty, and full-time contingent faculty on limited-time contracts (which may be renewed or not): “For adjunct faculty, unstable employment and the ever-present threat of contract nonrenewal means not only economic hardship because of wage insecurity, but also academic hardship. Simply speaking one’s mind in a public forum carries the risk of retaliation” (Howell, 2021, p.1 ). There is typically no formal grievance process for adjuncts. If one exists, at best, it is an inadequate one with no teeth. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) exists specifically to defend the free speech rights of students and faculty, including adjuncts: “Educators on college and university campuses must be free to speak their minds, ask tough questions, and facilitate learning without the threat of institutional censorship, coercion, or intimidation” (FIRE, n.d.). Without protections or proper compensation for adjunct instructors, it can be argued that the institution is in active conflict with those hired to profess and pursue ideological truths on its behalf.

Tenured faculty comprise the governing body of their academic departments. They also embody the ideological, political, and cultural fabric of their department and institution and are tasked with providing service components to develop and maintain that fabric. As part of this, they establish and maintain the ‘Research, Tenure and Promotional’ guidelines for those already in their ranks. Though adjunct and contingent faculty may sometimes serve on hiring committees, ultimately the decisions about who joins the ranks of tenure-track, adjunct and contingent faculty fall to the department Chairperson (tenured) and/or their Dean and/or their Provost. Therefore, those who already enjoy tenure are those who decide who to hire for open teaching positions at all levels. This power dynamic can pose potential problems:

Even when it affords some protection to faculty speech, tenure also creates a barrier to faculty hiring and promotion. It raises the stakes of new faculty hiring and introduces multiple opportunities for the faculty to veto or obstruct a potential candidate’s progress through an academic career. Ideological bias and discrimination are well-documented features of the higher education job market. … In these circumstances, tenure can also become a weaponized tool for excluding minority political perspectives from the hiring and promotion process. (Magness, 2021, p.1)

At the same time, it is important bear in mind the reasons tenure exists in the first place:

The impetus behind tenure is to support academic freedom: to protect researchers from being fired for political or social retaliation, or because their work is less exciting than other topics. The pursuit of knowledge is inherently tied to social and political contexts, and certain topics are considered unimportant by people who don’t work in that field, but research directions should not be determined by opinions. (Ishaq, 2021, p.1)

The tenure service component is also vital in shaping and governing topics such as equity, diversity and inclusion, student and faculty ethics, course offerings, learning outcomes and assessment, faculty council, budget priorities, and others that might otherwise be governed at the institutional level. Tenure service is thus (intended as) essential to maintaining academic and institutional democracy, ideological neutrality, and integrity.

The possible conflicts of interest in ‘who governs the governors’ here can be debated and are part of the ongoing tensions between adjuncts and tenured faculty. Tenure is an imperfect but crucial system. It is often considered a primary issue when debating the perils of adjunctification because it represents the inequalities of reward and privilege between equally capable and qualified professionals tasked with the identical jobs of educating students. This is a fundamental inequality that the institution must confront, but does not necessarily signal a false meritocracy at the departmental level:

The lived experience of many non-tenure-tracks destabilizes this narrative profoundly. They are frequently on the job market and experience a wide range of searches. They see first-hand how capricious and arbitrary the selection process is. They understand that “merit” is a malleable thing, and is determined differently by different departments, and even by different people within a single department. Because of the overproduction of PhDs in many areas of geography, most hires attract many qualified candidates, any of whom is entirely worthy of a tenure-track position. Departments make their selection from among these worthy candidates based on the department’s particular needs and values, which are wholly variable and unpredictable. (Purcell, 2007, p.129 )

The idea that departments or tenured faculty have any control over institutional policy when it comes to adjunct contracts is generally false. Departments are at the mercy of the institution regarding the rights and privileges of adjuncts. Therefore, debating academic policy and integrity as concerns the ‘mixed populations’ of adjuncts and tenured faculty within a given department is valid. But until tenured and adjunct/contingent faculty status changes at the institutional level, this fundamental fracture remains.

At this higher elevation of observation, “we have a better understanding of the consequences of adjunctification: the deprofessionalization of large segments of the professoriate, a diminishment in the quality of lower-division education and weakened protections for academic freedom” (Mintz, 2021, p.1 ). Building on this well-established premise (also see Michael Bérubé and Jennifer Ruth’s book, The Humanities, Higher Education, and Academic Freedom: Three Necessary Arguments (2015)) it seems to me that the burden of responsibility now shifts from the collective outsiders (adjuncts) and collective insiders (tenured faculty) to the institution itself. Corrections made to address the inequities of adjunctification and consequences of deprofessionalization may serve to bolster academic freedoms The University professes to embody and defend, but this solution must also in some radical fashion balance an equation wherein The University can afford to maintain itself financially and structurally. These corrections cannot be made unilaterally with any sustained success.

The moral challenge we face is not a Manichean contest pitting villainous administrators and trustees against an exploited workforce or a privileged professoriate versus an academic proletariat, but a much more profound conflict involving competing institutional priorities, market forces, vested interests and professional ideals. The status quo isn’t sustainable, but resolving this challenge will not be easy, especially in a context of highly constrained resources. (Mintz, 2021, p.1)

Effects of Adjunctification on Institutional Identity

How then does The University maintain (or perhaps rebuild) their academic integrity and at the same time collect enough tuition (as its primary source of funding) to survive financially? The University has also taken on complex, expensive social responsibilities it was not designed for including features and services such as mental and physical health support, student and faculty services, etc. which are now essential components of the business model, creating further layers of fiscal and liability issues. The self-imposed responsibility of producing students with ‘career and technical’ skills for the job market has also forced four-year institutions to further expand its infrastructure in an effort to attract more students.

While adjunct positions were originally a way to deal with an explosion in enrollment and expanding infrastructure costs, enrollment for the past few years have declined sharply and continues to decline in part because a college education is prohibitively expensive and in part due to the growing perception that “the value of an education in arts and letters is essentially gratuitous, and we have become the sort of people for whom a gratuitous value is, for the most part, no value at all” (Kaufman, 2015). (From a 2015 study by TIAA-CREF: “Approximately two-thirds of academics in adjunct faculty positions are in the liberal arts and one-third a professional discipline. One-half of liberal arts adjuncts are in the humanities (Yakoboski, 2015).”)

The University was not originally intended as a market for gaining skillsets to secure employment, but a place for research and study. This leads to the question of why universities are now considered the gateway to employment in any number of fields – a topic Dr. Daniel Kaufman explores in his excellent essay, Destroying The University:

The need for mass professional education could have been met by building upon the tradition of vocational education that we already have in this country. Rather than the budget-and soul-busting expansion of the University that we undertook, we might have expanded the two-year community college system, so as to include both blue-collar and white-collar job training. (Kaufman, 2020, p.1)

In response to consumers armed with grants and student loans, four-year institutions of higher education expanded from being cloistered destinations for privileged scholars to embracing an ‘education for all’ ethos. They bought land, added buildings and services, and became microcosms of society with ethical and moral missions. They expanded these missions to include service to their internal and external communities.At the same time, commercial marketplaces of education at these institutions subsequently diluted their own offerings and labor base.Additionally, more convenient and less expensive sources of technical and professional education continued to diminish the value of those programs at four-year institutions. The past two decades have been a series of contractions, mission re-alignments and resource re-allocations.

Can The (four-year) University correct or somehow outrun its negative fiscal trajectory and remain the same institution in terms of identity and purpose? Can the long-standing traditions of academic integrity and the marketplace needs of ‘education for all’ co-exist? Without massive endowments (including those with private interests in the products of research), an ever-increasing price tag on tuition and services, or the unlikely increase of federal and state support, adjunctification continues to be the primary stop-gap economic measure. But it is not enough. The University needs to directly address that the structure it has tried to protect through all this maneuvering will not sustain further challenges. A more fundamental institutional transformation must be enacted.

Rather than consolidate existing research on the topic of Institutional Identity, I feel it’s more relevant here to re-contextualize some of that thought through the lens of adjunctification. The problem with adjunctification is that it functions in contradiction to the principles of the institution: it is a practice that does not embody the highest standards of ethics, morality, and service to the community. Adjunctification is the lens through which The University can and must confront itself because otherwise it will continue to subvert its founding principles and become hollow. “To act responsibly, we must know who we are. If higher education today is uncertain about its social responsibilities, as seems manifestly the case, then this suggests that the American academy is unsure about its institutional identity (Sullivan, 2000).”

Before discussing what viable new directions of transformation might emerge from this train of thought, it’s important to further illustrate and emphasize how the structure and cultural fabric of The University has been challenged not just by overexpansion and subsequent market contraction, but by how adjunctification exposed further fundamental vulnerabilities.

Adjunctification and Historical Materialism

The driving factor in historical events [is] the economic development of society. Moreover, changes to the mode of production cause …social and political disruptions. In addition, other assets of a society like political institutions, customs, laws, morality, ways of thinking, etc., arise on the foundation of the economic. (Anuradha, 2022, p.1)

Not to lean in too hard on a Marxist analogy, but there are certain parallels between historical materialism and the current state of four-year institutions of higher education. Universities find themselves having to wrestle with fundamental shifts in their business model (and identity) based on economic pressures with the primary solution being a shift in the ‘mode of production,’ wherein adjuncts make up an increasing percentage of their workforce (44% of 1.5 million total faculty in 2020 (NCES, 2022)). Diversity, equity and inclusion are the new driving ideologies for institutions of higher education, and while those principles are meant to extend to all students, faculty, and staff, four-year universities have not yet addressed the many problems of the dual-class faculty system that works directly against those principles. This is the fundamental contradiction inherent to adjunctification.

The University is a class society, and it behaves like one. It has a two main rigid class structures, with administrative and faculty populations being symbiotic hierarchical pyramids. In each, there is more money and power at the top and less at the bottom. However, the adjunct is not a proletariat. Their aim is to take part in the existing institution without being exploited, and in fact, the adjunct aspires to enjoy similar benefits as enjoyed by the tenured ‘class.’ (Unionization is one of the solutions being explored but has yet to take hold in any substantial way).1

The University is also a cultural hegemony (a set of ideologies that maintains a capitalist state), with prevailing ideologies set by those who govern and agreed to by those who participate in the system. This is tricky in that if the dominant ideology shifts due to economic forces, it threatens the entire system: adjunctification is a (temporary) economic solution but also a growing potential threat to prevailing hierarchies and ideologies. It would undermine a university’s cultural integrity to have the faculty be entirely made up of adjuncts, so it is in their interest to maintain the tenure system to some degree. It is also in their interest to offer as many classes as possible (with tuition being the basis of the economy), and to do so, adjuncts are necessary. As the number of adjuncts grows, the proportion of those faculty representing and served by prevailing institutional ideologies and policies decreases, thereby causing fractures and conflicts.

The University finds itself trying to make a palatable argument for restructuring while maintaining its cultural and political integrity, and this dynamic becomes a battle over the soul of higher education. Does The University operate as a corporate model with top-down control, or as a traditional liberal model with a balance of power between administration and faculty and the free exchange of diverse ideas emanating from the faculty class? The liberal model may (perversely) be destroyed under the mission of ‘education for all.’ Once we accept that as a goal of higher education, the economic argument for adjunctification follows. On the other hand, if the institution adopts an ideology that doesn’t represent the body politic in an equitable sense, they become partisan (and potentially hostile) to the very people they profess to serve. Higher education cannot exist in an ideological vacuum and hope to still enjoy the faith of general society. (Tyndall, 2022)

The ‘assets of society’ in this analogy-the ‘customs, laws, morality, ways of thinking’ that shape institutions of higher education-are indeed what are being challenged. Economic forces disrupted the social and cultural missions of Academe, with socio-political forces now an increasingly larger component of that disruption; universities struggle with their own internal equity issues while trying to promote equity as one of their core values; the premise of meritocracy that tenure is based on is in question. This further complicates the new ideological and practical foundations of equity, diversity and inclusion being forged by universities. The University is a noble old idea that finds itself trying to navigate a modern egalitarian dilemma while in the middle of an expanding financial crisis. Adjunctification is where these concerns meet and is not just one of the issues these institutions need to resolve – it is the most critical one.

Ethical Restructuring

The fundamental issues of adjunctification can be summed up by the following two citations. First, “The new world I imagine is not radical but just; it is closer to the romantic ideal that I thought existed back when I was an undergraduate, before I realized that the corporatization of higher education has fundamentally flawed the idea of the university” (Kraft, n.d.); and second, from The Invisible Adjunct blog, “…if you allow the use of cheap, contingent labor, you will depress the wages (salaries) and degrade the status and working conditions of your guild (profession) members, and you will fail to maintain your labor monopoly. Let me emphasize: There is something deeply, structurally wrong with a profession that allows and even encourages the use of cheap, contingent labor” (Smallwood, 2004, p.1).

I’ve tried to eliminate bias from this overview wherever possible, but do recognize that my particular advocacy is being represented. My inclusion of the above quotes is meant to reflect the feelings of adjunct and contingent faculty in a collective sense and a specific range of discourse around adjunctification.

As someone who has spent ten years in the liminal space between higher education administration and teaching, it’s important to note that I do have personal and professional feelings about these topics These feelings come from direct experience on both sides of the issue. I work directly with department Chairs, Deans of Business and Operations, Deans of Students and Colleges, Human Resources, Risk Management and Legal, tenured, tenure-track and contingent faculty, part time lecturers, full and part-time staff, advisors, and students. I am also a lecturer, one that enjoys teaching as a part-time addition to my full-time job as an academic Program Manager. I am deeply fortunate. I worked hard to get here but know many equally and better qualified people who are still struggling to put together a stable career in higher ed.

I have on occasion bumped up against certain ceilings and boundaries I was unaware of while ‘showing initiative’ and had to be reminded that academia can sometimes be dismissive of those in ‘lower castes’. Those can be hard lessons. But in the end, there is no sinister master plan (that I am aware of). Tenured and tenure-track faculty, overall, consider themselves quite lucky to have secured those positions and do not perceive adjuncts or contingent faculty as being somehow ‘less than.’ Are there some who hold onto the idea of tenured ‘meritocracy’ as an equitable system that awards badges of class distinction? Sure. Are there some in upper administration who would have their universities take control and eliminate the complex system of checks and balances between those who teach and those who administrate? Probably yes, but I believe most people in higher ed see value in the system at the same time they recognize the flaws, believe there is a way to satisfy this equation, and see this as an historical moment of challenge and opportunity.

Adjunctification was a means created to address the demands of a higher ed bubble.Now that enrollments are declining, we are left with an oversaturated market. Adjunctification is not a system of servitude invented by institutions of higher ed, but it has become higher ed’s problem to own and solve.

The plight of the adjunct shows how personal success is not an excuse to excuse systemic failure. Success is meaningless when the system that sustained it – the higher education system – is no longer sustainable. When it falls, everyone falls. Success is not a pathway out of social responsibility. (Kendzior, 2013, p.1)

Consider the complex interplay of socioeconomics, ethics, politics, and philosophy at work in this single proposition from a colleague:

Is there a direct correlation between a rise in students with Liberal Arts degrees and national GDP (and individual earning power) over time, factoring in both student loan debt AND a model in which taxpayers fund higher education for all? If administration is making an economic argument for adunctification, do they have an ethical responsibility to prove that increasing access to college for all students really does have some measurable economic benefit to society? Do white collar job opportunities increase proportionally to the number of students with Liberal Arts degrees? Is producing ‘better citizens’ a justified argument for continued expansion of higher ed, and if so, at what cost to these ‘better citizens’ who become adjuncts?

Also consider,

Guaranteed federal loans also disrupt the normal market signals that would curtail rising education costs by eliminating the institution’s responsibility for realistic cost to benefit value for students. As long as all students can pay whatever the institution asks (with the consequences coming after graduation) the cost of higher education will continue to outpace inflation and earning potential. State funding for ‘education for all’ would only shift the burden from individual to the collective, but without real evidence that society will benefit economically from that investment, how do we justify this? Requiring students to be informed of debt to earning ratios for degree programs would be a good place to start — then at least a 19-year-old would have some hope of making an informed decision. (Tyndall, 2022)

It’s powerfully intimidating to even begin deconstructing this analysis into anything actionable, let alone a concerted program of reconstruction. But this is the state of things, for better or worse, and adjunctification is at the core of everything.It must be remembered that adjunctification, like education, revolves around people. However distorted or conflicted discussions may become around the Purpose of Education (Academe) and the Business of Education (Commerce), they are symbiotic and inextricable, and higher education is still a system meant to serve individuals, build societies, and protect ideas. Whatever path we take to keep those values intact is the right one.

Here’s one line of thought — by no means exhaustive or data-tested – that attempts to connect these interdependent issues and propose ways in which they might be addressed:

Let’s say we flatten the two-tier system of faculty appointments, eliminating adjunctification entirely and the perceived meritocracy and inequities of class. The market is still oversaturated with qualified candidates, but at least they now have (for the sake of this illustration let’s assume) an equal shot at full-time teaching positions in their chosen field of expertise. (How the marketplace absorbs graduates who don’t find employment in higher ed is another discussion, as is The University’s culpability in continuing to produce these surplus candidates who are often saddled with enormous debt). The University must still contend with hiring bias and issues of cultural / social / political representation in their teaching ranks, but with the tenure ‘class’ system eliminated and rank equity established, the internal conflict of adjunctification has been effectively resolved.

The University is still paying faculty to teach all the classes it needs to gather tuition dollars. However, having eliminated the cost-saving option of adjuncts, total labor cost (including benefits, retirement, research support, equipment, space, etc.) has greatly increased. Additionally, I can tell you from experience that there will often not be enough classes in each department for all those full-time staff to teach. (Enrollment rates fluctuate, so the number of classes that need to be assigned to faculty also fluctuates). We now employ an occasional surplus of highly skilled professional talent, but full-time teaching appointments come with a required service component that might be useful to our mission.

Perhaps this surplus talent is tasked with developing and teaching cross-departmental curriculum, further enriching the institution’s offerings. They might also be assigned to meaningfully engage in collaborative work that supports institutional research and missions. This work could include social equity and justice, environmental sustainability, artificial intelligence and teaching technologies, accessibility, and so on. This sort of cross-departmental, cross-disciplinary collaboration toward actionable goals benefits the entire system. Perhaps some of the products of these collaborations would have financial viability in the marketplace? Arts and Letters departments could cross-pollinate with Business and Marketing departments to develop community relationships that might produce additional revenue or sponsorship opportunities and build institutional relationships. Maybe we deploy this surplus talent to reduce costs in other areas: while it may not be in line with the traditional service component of a teaching contract, faculty might dedicate part of their service to departmental advising, assisting other teachers, mentoring at the college and high-school levels, doing outreach and recruitment work, etc.

Perhaps this surplus talent are assigned to a task force that addresses the still-existing supply and demand imbalance inherent to the higher education system itself, proposing further structural change (“self-reflexive transformational studies” or some such scholarly-sounding thing). Maybe tenure requires rotation through other full-time service and research positions outside of the home department; participating in other aspects of the system is highly effective experiential learning.

The position of tenure does not need to be restricted to tradition. It can evolve. We need to think differently about the entire system:

…transformative change in higher education requires nurturing intertwined practices of making-with and empowering innovative ways of being together, rather than retreating to the more comfortably rewarded “self-making” that stakes out the territory of “I” within a highly corrosive competitive landscape. We believe this can at once create a more fulfilling and supportive culture in higher education and elevate the quality of our work across the institutional mission areas of teaching and learning, scholarship and creative activity, outreach, and engagement. (Cilano et al., 2020, p.1)

There are many studies and programs of reconstruction that should be considered vital and urgent blueprints of change – they are intended to be activated by the boldest and most innovative institutions seeking transformation toward growth and survival. I would encourage further exploration of these concepts in sources such as2:

- Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership: An Initiative for Transformative Personal and Institutional Change

- Critical Intersections: Public Scholars Creating Culture, Catalyzing Change

- The Paradigm Project / Bringing Theory to Practice

I would also strongly contend that we are not listening to our students. Students could be helping us to radically rethink and address problems of declining enrollment, attrition, and general disillusionment with higher education. I say this in just about every meeting I attend; those in higher offices say they are developing studies, holding town halls, parsing the data, etc., but I don’t see any students at these meetings helping us solve the Big Problems. How are we supposed to keep them interested in what we offer if we don’t ask them what they want us to offer and how we offer it? In my classes, I often engage students in discussions about how and what I’m teaching and how the department in general is doing to support them. These students flood me with passionate calls for change in how we as educators and administrators listen and respond to them. In a single hour-long focused discussion group about the state of our program I collected dozens of thoughtful and truly transformative ideas from our students we would have never considered otherwise.

Because faculty and students are often generations apart, there is simply no way for us to understand what is important to our students unless we ask them, admit the limits of our knowledge, and engage them in helping us to be better educators. This is my mantra at meetings where we discuss proposals for change: truly listen to and truly care about your customers – they will tell you how to fix this. (I see faces react when I say ‘customers,’ but that is exactly what they are. It is not demeaning – it’s simply true). Faculty sometimes say, ‘students shouldn’t tell us what or how to teach them;’ I understand and agree with that to some extent, but I also think that if you aren’t listening and responding to your students – if you’re not respecting them as people – you’re not doing your job. Teaching is not about reinforcing what you already know by transmitting it; teaching (learning) is a collaborative activity.

The key is always rethinking what we offer, the way we offer it, and the value proposition behind it. As a liberal arts university, if your enrollment is declining, ask yourself the following question: Are we delivering the liberal arts in a manner that is compelling to students? If the answer is that you are teaching them as you always have, then it’s likely time to pivot. A critical part of every liberal arts institution’s business strategy must be to make the relevance of the liberal arts clear and compelling. That is not the job of marketing and admissions, but the role and responsibility of leadership, vision, and strategic execution (CREDO, 2019).

Activating these innovations would help but would not fully address the fiscal foundations and declining surpluses of institutions of higher education. Another plan of transformation would be required on that side of the equation. Since the government began reducing its support of public universities in the 1970’s, many institutions have come to rely on relationships with community partners. Donations, endowments, grants, and tapping into alumni networks are all common fundraising sources, but the competition for these resources is fierce, and there is little equity. Larger institutions with programs that generate higher earners in fields like medicine and law receive larger donations and institutions lacking these programs and/or serving low-income students are less likely to receive such support. Sports is also a big money-maker. The ‘arts and letters’ and ‘equity serving’ institutions are in a much tougher position for solving this equation. In the meanwhile, reductions must be made.

I have participated in recent discussions about the somewhat dire financial outlook at my own institution and have observed that there is an increasing focus on identity.When you need to seriously consider which parts of your budget to reduce or cut, it forces you to identify the essential components. Not everything can be saved and sacrifices must be made. But I don’t see this as being a process of attrition. I see it as a healthy (if difficult) reckoning with purpose and mission. Consider the previous thoughts here about transformative change as a way of elevating the quality of our work. This transformation must be from within and without, meaning that while we distill what is essential to our Purpose in higher education, we must transform both ourselves as educators and our infrastructural landscape. This begins to sound like the sort of inspirational boilerplate I’m used to hearing in ‘state of the institution’ meetings, but I mean it literally. We (educators, administrators, and institutions) must enact radical change. ‘Education for all’ is still the goal, but not ‘all types of education for all people in every institution.’ We cannot be everything any longer. When we decide what needs to be cut so that we can focus our energies and resources, we also determine what we need to build upon and strengthen – we define our identity, and from there we find our community. There will be loss. There will be pain. Transformation is messy. But again: higher education is a system meant to serve individuals, build societies, and protect ideas. It is an essential human mission worth protecting at all costs. Whatever path we take to keep those values intact is the right one.

Notes

- The College of Arts & Media at CU Denver has implemented some progressive ‘equity-based’ policies, including raising the pay for 3-credit courses to $5,000, establishing permanent salary raises for full-time Instructors (who make significantly less than Clinical, Research or Tenure-track Instructors), offering 3-year contracts to all Instructors who have taught for more than two consecutive years, and establishing stipends for non-tenured faculty service-based work like curriculum development and committees. They are also charging tenured faculty with updating the college’s By-Laws and RTP (Research, Tenure and Promotion) Guidelines, thereby reaffirming faculty and departmental self-governance and hopefully integrating further modern frameworks for equity.

- https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2022.2054175,

https://imaginingamerica.org/wp-

content/uploads/LLI_Year_Three.pdf, https://bttop.org/wp-

content/uploads/2022/08/Paradigm-Project-Overview-

June-2022-.pdf

References

Anuradha. (2022). What is the Difference Between Dialectical Materialism and Historical Materialism. Pediaa. Retrieved 2023, from https://pediaa.com/what-is-the-difference-between-dialectical-materialism-and-historical-materialism/

Cara Cilano, Sonja Fritzsche, Bill Hart-Davidson, Christopher P. Long. (2020). Staying with the Trouble: Designing a values-enacted academy. LSE Impact Blog. Retrieved July 2023, from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2020/04/23/staying-with-the-trouble-designing-a-values-enacted-academy/

CREDO. (2019). No Margin, No Mission. Retrieved July 2023, from https://www.credohighered.com/blog/no-margin-no-mission

FIRE (n.d.) What We Defend. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://www.thefire.org/defending-your-rights/academic-freedom

Howell, Jordan. (2021). How adjunctification undermines academic freedom, and what FIRE is doing to help. FIRE. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://www.thefire.org/news/how-adjunctification-undermines-academic-freedom-and-what-fire-doing-help

Inside Scholar. (n.d.) The Rise of Adjunct Faculty. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://blog.insidescholar.org/the-rise-of-adjunct-faculty/

Ishaq, Sue. (2021). A Brief History of the Brief History of Academic Tenure. The Ishaq Lab. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://sueishaqlab.org/2021/03/26/a-brief-history-of-the-brief-history-of-academic-tenure/

Kaufman, Daniel A. (2015). On Some Common Rationales for Liberal Education (and why they aren’t very good). Electric Agora (archive). Retrieved 2023, from https://theelectricagora.com/2015/10/19/on-some-common-rationales-for-liberal-education-and-why-they-arent-very-good/

Kaufman, Daniel A. (2020). Destroying the University. Electric Agora (archive). Retrieved 2023, from https://theelectricagora.com/2020/01/18/destroying-the-university/

Kraft, Tiffany. (n.d.) Critical Digital Pedagogy, chapter 17. Pressbooks. Retrieved 2023, from https://pressbooks.pub/cdpcollection/chapter/adjunctification-living-in-the-margins-of-academe/

Kendzior, Sarah. (2013) Academia’s Indentured Servants. Aljazeera. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2013/4/11/academias-indentured-servants/

Magness, Phillip W. (2021). The Myth of “Adjunctification” and Disappearing Tenure in Higher Ed. American Institute for Economic Research. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://www.aier.org/article/the-myth-of-adjunctification-and-disappearing-tenure-in-higher-ed/

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Adjunct. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved April 15, 2023, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/adjunct

Mintz, Steven. (2021). The Adjunctification of Higher Ed. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/higher-ed-gamma/adjunctification-gen-ed-0

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Characteristics of Postsecondary Faculty. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved July 2023, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/csc

Purcell, Mark. (2007). Skilled, Cheap and Desperate: Non-tenure-track Faculty and the Delusion of Meritocracy. Antipode. Retrieved July 2023, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2007.00509.x

Smallwood, Scott. (2004) The Invisible Adjunct Shuts Down Her Popular Weblog and Says Goodbye to Academe. Excerpts: Thoughts From the Invisible Adjunct. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.chronicle.com/article/disappearing-act/ (also see: http://www.invisibleadjunct.com/)

Sullivan, William M. (2000). The University as Citizen: Institutional Identity and Social Responsibility. The Civic Arts Review, Vol. 16, #1, Spring 2000. Retrieved July 2023, from https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1040&context=slcehighered

Tyndall, Edward. “See notes attached.” Received by Beeson, Christopher, November 15, 2022.

Wiktionary. (n.d.) Adjunctification. Retrieved 2022, from https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/adjunctification

Wordsense. (n.d.) Adjunctification. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://www.wordsense.eu/adjunctification/

Yakoboski, Paul J., Ph.D. (2015) The Career Experience of Academics in Adjunct Faculty Positions. TIAA-CREFF Trends and Issues, May 2015. Retrieved July 2023, from https://www.tiaa.org/content/dam/tiaa/institute/pdf/full-report/2017-02/adjunct-career-experience-full.pdf